Lunar maps, 1970s.

Tuesday, July 30, 2013

TSCHUMI

|

Bernard Tschumi

The Manhattan Transcripts

1976-1981

The Manhattan Transcripts

1976-1981

"Architecture is not simply about space and form, but also about event, action, and what happens in space.

The Manhattan Transcripts differ from most architectural drawings insofar as they are neither real projects nor mere fantasies. Developed in the late '70s, they proposed to transcribe an architectural interpretation of reality. To this aim, they employed a particular structure involving photographs that either direct or "witness" events (some would call them "functions," others "programs"). At the same time, plans, sections, and diagrams outline spaces and indicate the movements of the different protagonists intruding into the architectural "stage set." The Transcripts' explicit purpose was to transcribe things normally removed from conventional architectural representation, namely the complex relationship between spaces and their use, between the set and the script, between "type" and "program," between objects and events. Their implicit purpose had to do with the 20th-century city."

Labels:

city,

composition,

frame,

mapping,

photography,

sequence

DANIEL LIBESKIND

More on his work and process here.

|

Micromegas, 1979 |

|

Daniel Libeskind. Edge City, 1987. |

Sunday, July 28, 2013

JAMES CORNER : MAPPING

James Corner is an American Landscape Architect and theorist. His 1999 essay The Agency of Mapping; Speculation, Critque and Invention in Mappings explores the potential creative capacity of mapping processes.

“As a creative practice, mapping precipitates its most productive effects through a finding that is also a founding; its agency lies in neither reproduction or imposition but rather in uncovering realities previously unseen or unimagined, even across seemingly exhausted grounds. Thus mapping unfolds potential; it re-makes territory over and over again, each time with new and diverse consequences.”A pdf copy of the essay is available online here

The drawings in this post are taken from James Corner's book; Taking Measures Across the American Landscape

Tuesday, July 23, 2013

GORDON MATTA-CLARK

|

| Conical Intersect. |

"Completion through removal.

Abstractions of surfaces.

Not-building, not-to-rebuild, not-built-space.

Creating spatial complexity, reading new openings against old surfaces.

Light admitted into space or beyond surfaces that are cut.

Breaking and entering.

Approaching structural collapse, separating the parts at the point of collapse"

- Gordon Matta-Clark, 1971

Best known for his large-scale “building cuts,” which radically altered architectural sites, Matta-Clark investigated space using a number of strategies and media.

He chopped up abandoned buildings, making huge, baroque cuts in them with chain saws, slicing and dicing like a chef peeling an orange or devising radish flowers. (The food analogy wasn’t lost on him.)

|

| Splitting |

"To a plain single-family suburban frame house in Englewood, N.J , Matta-Clark made a cut straight down the middle, bisecting the building, then severing the four corners of the roof like so many trophy heads. It was spectacular but not quite like the times he sawed tear-shaped holes into floors of an office building in Antwerp, or conical openings into a pair of antique houses in Paris slated for demolition next to where the Pompidou Center was being built. What resulted were vertiginous, Piranesean spaces, uncannily beautiful and kinetic, preserved on film and in drawings and in collaged photographs that, as you can see in the show, are like Rubik’s cubes or Eschers."

via The New York Times

The conical shape of the cuts has a strong resonance with the geometry of optics,

perspective and image-making technology. Matta-Clark himself described the shape as a

“spyglass,” through which to see things in new, secret ways.

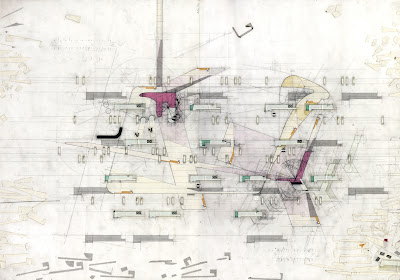

PERRY KULPER

|

| Central Califoria History Museum, Thematic drawing |

|

| Thematic Drawing, detail |

Perry Kulper is also a teacher, and has taught courses similar to this one. Below are a range of works by students in one of these courses.

Project: Generative Removal

These projects focus on erasure as a means of generating an architectural proposition. Instead of contributing to architecture through additive means, the erasure work attempts to produce architecture through subtractive methods. Perry introduces an idea of “5 points of erasure as deconstructing towards a new architecture” which he likens to Le Corbusier’s “5 points of architecture.”

The work started by creating a diptych which, on one side, had the floor plan of a famous villa or house. The other side of the diptych was to be populated with a series of “marks” whose character and placement was determined by a series of rules. Once the diptych was populated with marks, the work of erasure could begin. Again, a very specific set of rules was used to govern the removal and/or remembering of the marks. The two sides of the diptych were governed by the same rules and meant to be worked as a single drawing.

BRUNELLESCHI & A SENSE OF SPACE

|

Perspective drawing for Church of Santo Spirito in Florence,Brunescelli, c.1428, early renaissance |

|

| reconstruction of Brunelleschi's first picture in perspective, Samuel Y. Edgerton, (1975) |

|

| reflection of the perspective drawing of the Florentine Baptistery in the mirror experiment of Brunelleschi |

|

| ‘Herod’s Feast’ by Masolino (1436); ‘The Annunciation’, by Fra Carnevale (1448); ‘The Flagellation of Christ’ by Piero della Francesca (1453). |

Bruneschelli observed that when you have a fixed, single point of view, parallel lines seem to converge at together at an imaginary point in the distance. He then applied this idea of a single vanishing point to a canvas, and discovered a method for calculating -and drawing - depth. Bruneschelli's famous experiment used mirrors to aid him in sketching the Florence baptistry in perfect one-point perspective.

Prior to Bruneschelli's observations, artists either avoided depicting space, producing flattened images, or attempted to produce space using other means, often resulting in skewed space. While Bruneschelli's perspective might be the most 'correct' in the sense that the images produced reflect what the human eye sees, other methods of depicting space, including ones which might not yet be discovered, are also valuable

In making

his first depiction of Florence

These drawings address begin to not only the solidity of physical form but also the flow of architectural possibilities and spatial contingencies.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Shaoxuan Dong

Shaoxuan Dong Harry (Me)

Harry (Me) Xiang Liu

Xiang Liu Catharine Pyenson

Catharine Pyenson Harry

Harry Jeeeun Ham

Jeeeun Ham